How Risky is Pain Treatment?

Pain Care Part 1: Exploring the Benefits & Risks for 2 Common Pain Treatment Options for Injured Workers

We are used to commonplace things working: stoves, electronic gadgets, our cars. We complain about glitches yet they really rarely happen. However, this is not the case when an injured patient seeks pain relief – treatment can often fail. Even worse, medical care can be iatrogenic, meaning that the treatment creates new health problems in addition to the original injury. These problems include side effects from taking prescribed pain medications as well as complications from surgery.

Consider how experts in pain care have taught themselves about the risks of pain treatment and how their research has gone on to impact the workers’ compensation community.

They usually share studies, published sometimes years before the general public is made aware of them. For instance, the workers’ compensation community began to pay close attention to the risks of opioids around 2010, ten years after researchers in the late 1990s first detected that patients were dying from opioid prescribing. After 2010, the workers’ compensation community began to issue state prescribing practices and to ask for urine drug testing.

Escalation of Opioid Rx

By then, some 15,000 people throughout American society were dying each year from misadventures with prescribed opioids. And in 2015, opioids killed more than 33,000 people, more than any other year on record. While no one has counted how many of these deaths arose out of opioid use among injured workers, in all likelihood several hundred injured workers a year were dying, some having been on opioids for pain treatment for years.

By then, some 15,000 people throughout American society were dying each year from misadventures with prescribed opioids. And in 2015, opioids killed more than 33,000 people, more than any other year on record. While no one has counted how many of these deaths arose out of opioid use among injured workers, in all likelihood several hundred injured workers a year were dying, some having been on opioids for pain treatment for years.

In the past dozen years or so, pain experts have learned a great amount about prescribing practices. For example, a study of California showed that a very small percentage of those who prescribed – less than five percent – accounted for a huge share of total prescriptions to injured workers.

More specifically, pain experts started to look closely at whether opioids were effective for treating common work-related conditions such as back, shoulder, or knee pain. But researchers had difficulty finding evidence that opioids provided benefits for long term pain relief. In fact, some reported contrary findings – one study showed that long term use of opioids often caused the patient to become more, not less, sensitive to pain signals.

These studies prodded states to limit prescribing through the use of a formulary, which is a formal list of drugs that workers’ comp will pay for. Texas and Washington are two examples among many other states that introduced formularies to cut down on opioid prescribing. Their formularies were effective as opioid prescribing did decline. This decrease allowed patients to be exposed to more drug-free pain treatment options; which did not have the risks and side effects of opioids such as: drowsiness, constipation, stress and addiction.

Next Stop: Spinal Surgery

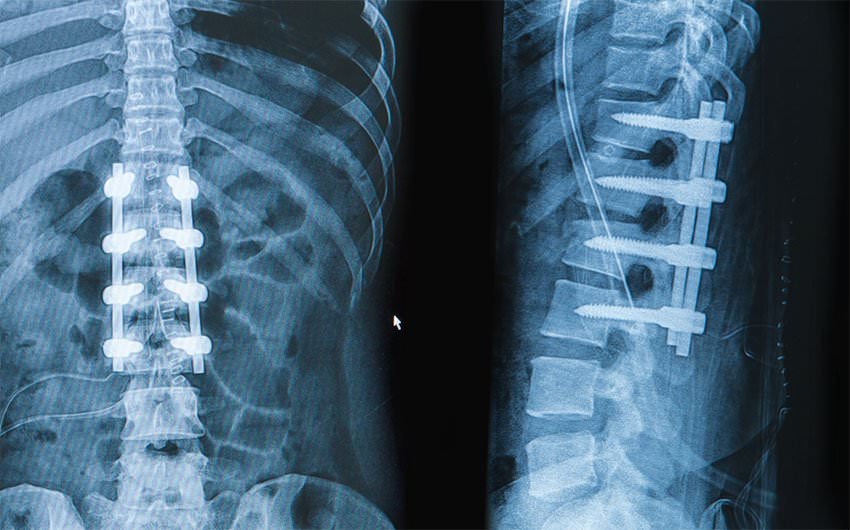

At about the time that opioids came to the market in a big way, surgeons began to promote more aggressively surgical cures as pain treatment. One of the leading surgical innovations was spinal fusion, which fuses together two or more vertebrae, restricting movement. Spinal fusion advocates say that the procedure can remove pain, and therefore exist as an effective pain treatment.

At about the time that opioids came to the market in a big way, surgeons began to promote more aggressively surgical cures as pain treatment. One of the leading surgical innovations was spinal fusion, which fuses together two or more vertebrae, restricting movement. Spinal fusion advocates say that the procedure can remove pain, and therefore exist as an effective pain treatment.

However, some studies of injured workers suggest that this is not the case. One study of injured workers in Ohio found poor outcomes from spinal fusion. Only a quarter of workers with this procedure returned to work within two years. And another quarter had to have a second operation. Alarmingly in these cases, opioid use went up, not down, after surgery. As with any surgery there are high risks and high costs; and as these case studies reflect, can accompany a trend of increased opioid use. Therefore best practice treatment guidelines today caution doctors to consider the risks of spinal fusions.

So, over the past twenty years, we have seen a cycle of opioid prescribing going up and back surgery becoming more prevalent. These two forms of pain treatment are well known, but certainly not the only options available. There are less invasive, less risky options including but not limited to: physical therapy, electrical stimulation, and guided exercise. The emphasis to recommend these two treatments stems from the research that pain experts highlight about effectiveness and possible risks. This research has shown to be a major influence for opioid prescribing and surgeries.